Sacred Choral Composition: Southeast Asian Idioms and/for a Scottish Collegiate Choir. Presentation by Kenneth Tay

This presentation explores the emergent opportunities for innovation in sacred choral music through the integration of Southeast Asian musical idioms, thereby promoting cultural inclusivity and enriching liturgical practices. Despite increasing interest in global(-ised) music practices, there remains limited exploration into how Southeast Asian musical traditions can be effectively incorporated within sacred choral settings, particularly within collegiate choirs trained in Western paradigms. The objective is to investigate the potential for Southeast Asian idioms, such as vernacular texts and drone-melody structures, to inform sacred choral compositions, fostering intercultural dialogue and theological reflection that challenges established Eurocentric norms.

Employing a practice-led research method, this study involves a collaborative effort with the University of Glasgow Chapel Choir from 2023 to 2025. The approach includes compositional experimentation and reflective analysis grounded in liturgical contextualisation frameworks (e.g., Loh I-to, Lim Swee Hong) alongside postcolonial critiques (e.g., José Maceda, Kok Roe-Min, Peter Phan, Grace Nono). Experiential insights from the creative process reveal that integrating Southeast Asian musical traditions necessitates a collaborative adaptation process to address issues of accessibility and cultural unfamiliarity within Western-trained choirs. The integration of Southeast Asian idioms into Western sacred choral music not only fosters theological dialogue but also highlights the fluid nature of authenticity and tradition. By positioning sacred choral music as a dynamic site for cultural exchange, I explore the contemporary sacred choral repertoire for its potential to deepen intercultural connections between diverse musical traditions and communities.

Sacred choral music has long been a site for cultural and theological expression, but its development has often been shaped by the historical dominance of Western liturgical forms. My research as a composer seeks to challenge this narrative by exploring how Southeast Asian idioms can be integrated into Western sacred choral music. Through collaborations with the University of Glasgow Chapel Choir, I have been engaged in a practice-led investigation into the possibilities of cultural hybridity in sacred music, with a hope to create compositions that bridge diverse traditions.

My discussion today operates at the intersection of transnationalism, cultural hybridity, and the collaborative nature of choral singing. Transnationalism positions sacred music as a medium that transcends cultural and national boundaries. By introducing Southeast Asian musical styles into the programme and repertoire of a Scottish collegiate chapel choir, my work highlights the permeability of choral music traditions and their ability to adapt and evolve in globalised contexts. I draw inspiration from scholars such as José Maceda and Loh I-to, who have championed the reclamation of Indigenous Southeast Asian traditions in sacred and art music.

Finally, my session today emphasises the collaborative essence of choral singing. The University of Glasgow Chapel Choir, composed of non-professional singers trained in Western liturgical music, serves as both performer and partner in the creative process. Their engagement with unfamiliar musical structures highlights the participatory and adaptive nature of choral singing, revealing its potential as a cultural laboratory for experimentation and inclusivity.

By integrating these perspectives, my work contributes to an ongoing conversation about the future of sacred choral music, advocating for its evolution as a site of cultural exchange, theological reflection, and community building in a transnational world.

Here in this photo is something that might at first glance look a bit unusual - the Holy Trinity Anglican Church in Singapore, which was built by Fuzhou and Hokkien speaking congregations. Curiously, you’ll find Han Dynasty (歇山顶, xiēshān dǐng) style sloping roofs.

In the postcolonial era, Asian churches have exhibited great enthusiasm and determination in asserting their unique voice in the broader context of World Christianity. I note that while most Asian churches are independent in their governance, financial, and ministry structures, this has not been in the case for music. Instead, Asian churches continue to use music inherited from their missionary-based origins, often suppressing local expressions. [1]

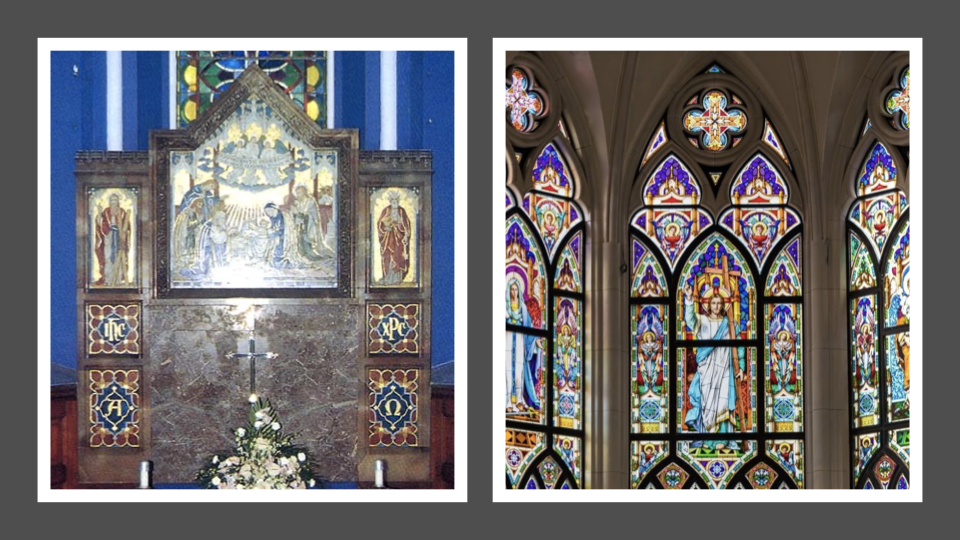

Perhaps some part of the colonial vestiges are more apparent in the visual arts. On the left is the nativity chapel in St Andrews Cathedral in Singapore. The mosaic made in Italy shows the shepherds at the birth of Christ in Bethlehem. On the right is the stained glass of the Church of St Alphonsus in Singapore. Since the evangelistic message was so intricately bound to Western expansionism, the image of Jesus remains that of “colonial Christ” [2] – a white man with blonde hair and blue eyes; that Jesus was in fact a Middle-Eastern Jew is rarely considered, or represented in many Asian churches. In terms of music, local congregations have forged their Christian identity via translated Western hymnody, whose formation upheld the premise that their own cultural music was inappropriate for Christianity’s use. Lim Swee Hong explains that the continued reliance on Western worship music post-colonialism and the perceived alienation from local cultures when embracing Christianity suggests a historical dynamic where being Christian has often been associated with Western practices, potentially influenced by socio-cultural realities and the need to navigate less hospitable environments. [3]

From the 1990s, the prevailing trend of Christian spirituality leaned more towards American and Australian-style evangelicalism. One of the reasons was the strong influence of contemporary Christian worship music, in particular, coming out of Hillsong from Sydney, Australia, whose musical sound has influenced numerous denominations across Asia. As a result, the pursuit of mass participation in corporate worship took precedence over the exploration of local expressions.

This led Loh I-to, one of Asia’s foremost church musicians and ethnomusicologists to write, “We have paid a heavy price to be Christians. It would appear that when we choose to be reconciled with God, we become alienated from our own culture and if we choose to be culturally grounded we risk being alienated from God. Sadly, the majority of our churches appear to have this implicit attitude.” [4]

The need for contextualisation becomes particularly pressing when viewed through a postcolonial lens that critiques the historical imposition of Western musical forms during colonial and missionary activities, which often marginalised indigenous practices. Maceda, for instance critiques the Eurocentric hierarchy that positioned Western classical music as "high art," relegating Indigenous Southeast Asian traditions to the realm of "folk" or "primitive" music. He argues that this cultural imposition devalued the spiritual and artistic worth of Southeast Asian musical systems, often leading to their exclusion from a variety of sacred settings. [5]

In broader societal trends, colonial attitudes have persisted and continue to play a significant role in shaping certain musics as more desirable than others, if not explicitly.

In many ways, I have been a part of that system, dutifully following the graded exam system of the ABRSM. Kok Roe-Min critiques systems like the ABRSM exams, which perpetuated Eurocentric ideals of musical sophistication, with the graded exams serving as a tool for social mobility and cultural capital, whilst sidelining local music traditions as non-productive to pursue. In societies like Malaysia and Singapore, Western classical music is often uncritically adopted as a marker of sophistication and social mobility, overshadowing local traditions. [6]

Still today, words like parochial, backward, ignorant, untrained, primitive, irrational, undeveloped and unintelligible are unfortunately some of the adjectives used to describe the qualities of local music traditions. Grace Nono, a Filipino ethnomusicologist, and scholar of Philippine shamanism, summarises, and I quote: “that's what colonialism does, it attempts to destroy people's sense of self, history, memory… regardless if you are coming from the inside or the outside, especially if you are promoting matters that many Indigenous peoples themselves have also come to demonise, like those pertaining to native rituals. Because we have all been made to believe that our ancestors were demons. And the only way that we can be saved is by severing our ancestral ties and by embracing the coloniser's ways.” [7]

From the lens of postcolonial critiques, contemporary sacred music demands a re-evaluation. It is not lost on me that I am presenting this critique as someone pursuing a PhD in music at one of the institutions deeply embedded within the very Eurocentric framework I am interrogating – the RCS is after all a member of the ABRSM. This irony, however, is precisely what underscores the complexity of postcolonial discourse. Engaging with these structures from within allows me a more nuanced re-evaluation of inherited hierarchies. Rather than rejecting Western classical training outright, my work seeks to interrogate its dominance, making space for alternative epistemologies that have long been marginalised. In this way, my goal is not resistance, but a constructive re-imagining of sacred music traditions that honours both global, transnational influences, with I hope, indigenous integrity. Sacred music must resonate with the lived realities of the communities it serves: a hallmark of contextualisation.

Where does my work as a composer lie? I begin by situating my work as a composer of sacred music within the framework of liturgical contextualisation, which involves adapting worship practices to reflect the cultural and spiritual identities of specific communities. This concept seeks to move beyond the dominance of Western liturgical forms, fostering worship that is culturally authentic and theologically meaningful. Writing in the 1980s, Loh I-to formulates the paradigm of contextualisation in the context of Asian hymnody through the following approaches: [8]

- Indigenous: Expanding the potential of native materials and techniques in composition

- Syncretistic: Harmonising native melodies with fourths and fifths, and providing linear counterpoint, thus avoiding the effect of traditional western harmony

- Confessional: Utilising the best innovative, contextual and international artistic skills and expressions

Loh’s concern for the preservation and innovation of indigenous music is evident in the design of this paradigm. Also present is his presupposition of minimising western musical elements in the effort of contextualisation.

What then is the compositional “signature” of Southeast Asia? Maceda argues that Southeast Asian musical traditions, characterised by repetition (drone and ostinato) and a focus on timbre and pulse rather than linear melodic development, reflect a non-linear, metaphysical understanding of time connected to nature and the divine. [9] He examines various musical forms and ensembles across the region, illustrating how melodic ambiguity and a sense of continuity differ from the goal-oriented, hierarchical time structures found in Western music, particularly those influenced by principles of causality and harmonic progression. Ultimately, he posits that Southeast Asian music embodies a different temporal experience, one rooted in cyclicality, infinity, and a harmonious relationship with the natural world, offering a contrast to the linear, progressive notion of time often underpinning Western thought and music.

For the purposes of this presentation, I've summarised Maceda's key arguments in a table-format comparison to illustrate the characteristics of Southeast Asian music:

Here are some examples of Southeast Asian music traditions. In the first, :

I now turn to a review of my work as a composer alongside a collegiate chapel choir.

The University of Glasgow Chaplaincy and Chapel Choir offer a uniquely hospitable environment for my work as a composer integrating Asian musical gestures into Western sacred choral forms. The Chaplaincy’s remit, as articulated by the director of music, Katy Lavinia Cooper, embraces plurality, liminality, and presence, cultivating a space that privileges listening, hospitality, and the flourishing of personal and communal meaning-making. [10] For instance, alongside the two full-time university chaplains, there are 16 honorary chaplains from different faith backgrounds that the chapel team works closely with. I find that this openness to a non-confessional, non-prescriptive approach to providing support to its university community fosters a fertile setting for sacred music that resists liturgical homogeneity. My compositional practice, which draws from Southeast Asian spiritual idioms and musical vocabularies, is able to find resonance within this ethos, contributing to the Chaplaincy’s vision of worship and community as dialogical, layered, and porous across cultural and theological boundaries.

Here are some examples of some of my compositions that have been performed with the Chapel Choir. I hope that in some of these examples and through my practice, I demonstrate how choral music operates as both a transnational phenomenon and a participatory practice, creating a unique space where cultural identities, theological narratives, and communal engagement intersect.

Notes

[1] Lim, Swee Hong. “Just Call Me by My Name: Worship Music in Asian Ecumenism.” The Ecumenical Review 69, no. 4 (2017): 502–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/erev.12317.

[2] Phan, Peter C. “Jesus the Christ with an Asian Face.” Theological Studies 57 (1996): 399–421.

[3] Lim, Swee Hong. “Asian Christian Forms of Worship and Music.” In The Oxford Handbook of Christianity in Asia, edited by Felix Wilfred, 524–38. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

[4] Loh, I-to. “Contextualized Music in Worship: My Mission.” Theology and the Church 2, no. 1 (1994): 113–132.

[5] Maceda, José. “The Place of Asian Music in Philippine Contemporary Society.” Asian Studies 1 (1963): 71–75.

[6] Kok, Roe-Min. “Music for a Postcolonial Child: Theorising Malaysian Memories.” In Learning, Teaching, and Musical Identity: Voices across Cultures, edited by Lucy Green, 73–90. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2011.

[7] Nono, Grace. Music, Voice, & Healing: A Conversation with Grace Nono. Transcendence and Transformation Initiative, Harvard Divinity School, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E8sN_35CgHE.

[8] Loh, I-to. “The Emergence of Asian Styles in Asian Hymns.” Paper presented at the International Hymnological Conference, American Hymn Society and British Hymn Society, Moravian College, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, August 1985.

[9] Maceda, José. “A Concept of Time in Music of Southeast Asia: A Preliminary Account.” Ethnomusicology 30, no. 1 (1986): 11–53. https://www.jstor.org/stable/851827.

[10] Cooper, Katy Lavinia. “Chaplaincy, Context, and Community Building: Christian Worship, Music, and Human Community.” Seminar, The Institute of Sacred Music, St Stephen’s House, University of Oxford, 2023. https://www.rscm.org.uk/whats-on/ismo-seminar-series/.

.png)

Comments

Post a Comment