(dis)embodied transnationalism? – a lyric in the Euing Collection. Presentation by Ashley Holdsworth Quinn

|

| GB 249 T-MIN/7 University of Strathclyde Archives and Special Collections. Reproduced with permission. Photograph by AHQ. |

Buried deep in the archives at Strathclyde University is a fragile, but otherwise unremarkable looking sheet of paper. At the bottom of the text is a note, in English, labelling it ‘A Russian Song’

|

| Extract from GB 249 T-MIN/7 |

On the paper is a set of handwritten lyrics, apparently dictated by one person to another less familiar with the language of dictation – several scratched-out and rewritten passages suggest a process of listen-write-repeat. Intriguingly, the lyric is also offered in a Latin translation on the same page. This is all we know about the document – what it is, and where it can be found. Author, context, title, even the music itself are missing, and the extant records reveal minimal information about how a Russian song came to be preserved in a Glasgow archive.

This short paper proposes two questions. The first considers the transmission of music as an embodied practice. The second considers the role of digital archives as a meaningful resource, albeit not without their own problems. Finally, we will hear a restored version of the song.

Background to this research

At this point, a word explaining why I’m interested in this document may be in order. I have been a member of Cappella Slavonica Scotiae (formerly known as Russkaya Cappella) since 2013, and have been in love with the repertory of Eastern Europe since my teenage years, when walls were coming down and people were able to encounter each other, and their music, in a way that had been impossible in the decades previous. [1] By 2019 I was thinking about pursuing a PhD in Scottish–Russian musical encounters, and had started looking through the Scottish Archive Network’s online resources for archives or material that might prove fruitful. [2] The search yielded various pieces of information, notably choral material prepared by Archibald Henderson, [3] organist at the University of Glasgow around the time of the First World War. Perhaps not entirely coincidentally, this was the exact period in which the University commenced teaching Russian. [4]

|

| William Euing, Underwriter, Bibliophile, Singer. |

I had been hopeful that the collection of nineteenth century Glasgow businessman William Euing might include material from Russia; his Will included ‘several thousand volumes’ of ‘music and works on music’ to be left to the University of Glasgow and Anderson’s University, now the University of Strathclyde. [5] I had a look at the online catalogues and learned there are indeed c. 17,000 individual pieces of music, mostly transcribed by hand and bound into volumes now held at the University of Glasgow. Of these, only two were relevant to the search: from such scant yields I believe it is fair to infer that Russian music was not of particular interest to Euing. However, the existence of these two pieces demonstrates a musical connection, albeit gossamer-thin, between Russia and Scotland in the first half of the nineteenth century. By studying the physical documents and their contents it is possible to generate an imaginary map of the journeys undertaken by these songs.

|

| Courtesy of University of Glasgow Archives and Special Collections, Euing Collection, MS Euing R. d. 33 . |

The first of the documents, held at the University of Glasgow, is titled Russian Air, with subtitle ‘An Ukrainian Song’. Obviously this is today a contested label, and the issue deserves more than a 20 minute paper to discuss properly, so I don’t propose to address it here. However, having looked at the music it was immediately recognisable as a version of a song called Їхав козак за Дунай [Ihav Kozak za Dunai], translated as From the Danube Was He Riding. The lyric is by Ukrainian poet Semyon Klimovsky, and music by Aleksandr Yegorovich Varlamov. [6] The English text is a reasonably faithful translation (by a mysterious ‘Count Crestawitch’, whose identity I have been unable to confirm) of Klimovsky’s story of a Cossack parting from his lover in order to participate in a glorious battle, to her dismay. The melody might be familiar (click link for recording):

English text from the Euing Collection version of the song, trans. Count Crestawitch.

1

From the Danube he was riding

When I crossed his path today

Straight the spur his war-horse riding

Speed! he cried away

Dear Cossack! My steed detaining

Stay – and hear thy girl complaining

See my cheeks how tears are staining

Dear Cossack! Oh stay –

2

“Well thou know’st when last we parted

Dearest! What distress was mine

Almost was broken hearted

Now the turn is thine.”

Dear Cossack no longer grieve me

Ah my love! How canst thou leave me

Grief with love of life bereave me

If I thee design

3

“Break not these thy hands with wringing

Halt the sob and dry the tear

Soon from Battles laurels bringing

Love! expect me here”

Battles fought with blood alarm me

Glory cannot tempt or charm me

Oh there’s nought in life can harm me

Wast thou save – my dear –

4

Vain were prayers and vain was sorrow

Swiftly from me sight fled he

Saying if I live tomorrow

I’ll return to thee

Then with folded arms and sighing

Home I wandered almost dying

How I found my way with crying

Still is strange to me –

This melody is frequently known in Europe as Schöne Minke, and it has been referenced by composers of the Western canon including Beethoven [7], Victor Magnien (guitarist) [8], Hummel [9]. Its reception history across Europe has also been fairly well documented by historical musicologists specialising in Beethoven’s song commissions [10], and by those working on material from Ukraine, such as Stanislav Tsalik. [11]

|

| Does Beethoven really need a caption? Portrait by Joseph Karl Steiler. |

The second piece, held in the University of Strathclyde and shown at the top of the page, is in some ways much more intriguing. As noted above, the document was identified through the Scottish Archives Network (SCAN). [12] SCAN was created in the earliest years of this millennium as a Heritage Lottery Funded initiative to ‘put Scotland’s archival history on the Internet and provide a model for access to archives in the early twenty first century.’ [13] The project created a database of archival holdings across Scotland, including material from the National Archives, local authorities, businesses, religious organisations, land estates, universities. Contents were in many cases listed in granular detail, to fonds level. The database, however, ceased to be updated after 2004, although the existing content was maintained, and searchable. In January 2025 the entire digital catalogue was transferred to National Records of Scotland, which now supports archived website as part of its Web Continuity Service, leaving the SCAN website derelict of its search function. The Network’s history has therefore evolved from pioneering digital resource in the years after the Millennium, to a mothballed site that was not updated for two decades, to a heritage item managed by a governmental custodian.

|

| Screenshot of the old SCAN landing page. |

Returning to our lyric, SCAN described the document as part of a collection which ‘consists of 8 pieces of sheet music dating from the mid-18th to late 19th century.’ [14] These eight items can be briefly summarised as two operatic arias by Handel, several French songs, two songs from the English theatre, ‘La Romeka’, a Greek dance tune, and finally our document, ‘Words for a Russian Song. So, it’s a small but geographically and stylistically eclectic collection of pieces that do not appear to have much in common other than where they are held: Archives and Special Collections at the University of Strathclyde. However, the SCAN listing went on to note:

This small collection of sheet music by various composers appears to be mid 18th-early 19th century in origin, and although some (such as the 'Russian song') may possibly be linked with Professor John Anderson, it is more probable that the collection was originally part of the Euing musical collection bequeathed to Anderson's University by William Euing in the 1870s and now housed in the Special Collections Department of Glasgow University Library.

|

| John Anderson, founder of Anderson's Institution, now the University of Strathclyde. |

This complicates matters further: if the contents of the document are unknown, and its provenance impossible to identify, can we derive anything of value from this mysterious lyric? I propose that, viewed through the lenses of embodied music making, and digital, ie accessible archival resources, it is possible to understand the music’s potential journey from Russia to Scotland (and back), and also to locate the notated music.

At this point it is worth noting that by the term ‘transnationalism’ within a musicological context I am very broadly following Krister Malm’s [15] framework, which understands the development of cultural exchange in tandem with technological and economic development. Keith Negus and Patria Román Velázquez develop the idea of music as a driver that allows identities to entwine; [16] ‘Two issues soon become interwoven and tangle; the identify of the music and the identities of the people and places associated with that music.’ This is a significant issue for our document; while we have no information about the people associated with it, it is, as we will see shortly, possible to construct a network of transmission across time as well as geographical space. Philipp Ther goes further in his analysis of transnationalist historiographies, finding that the theoretical framework it offers can yield broader possibilities to historians who wish to move beyond a national paradigm, pursue interdisciplinary study, or focus on linguistic or minority groups who have historically been omitted from the discourse. [17] Ther points out that networks of contacts in early nineteenth century Europe ‘were the basis of communication and learning processes over large distances, which have been of particular relevance for Central and Eastern Europe’; it is worth noting that Vienna, adopted home of Beethoven (remember Schöne Minke?) and host city of the Congress in 1815 following the end of the Napoleonic Wars is identified as the major continental locus of transnational interaction at that time: many nodes in many networks lived or corresponded with Viennese musicians. Moving from models of literary exchange to processes of embodied transfer we can usefully look to Björn Heile, who, while focussing primarily on global networks within musical modernism, notes the activated, even embodied processes inherent in music: ‘global music scholars have emphasised that ‘cultural transfer’ is an active process that requires musicians and composers to translate innovations in their specific contexts which involves a complex negotiation between local traditions and imported models.’ (My italics) [18]. Arnie Cox, [19] following Lakoff and Johnson’s [20] work on language, mind, and metaphor, draws a parallel between the mimetic process of learning music and learning a language, again emphasizing the active nature of listening. It is this relationship between text and music, words that are spoken and words that are sung, the activated voice and attentive ear, that surely gives us insight into the meaning derived from the lyric by whoever wrote it down and left if for us to find two centuries later in the Euing Collection?

So, what is so special about the lyrics, and where is the music?

Let’s first examine the paper itself. A single sheet, much folded; some of the folds are too tight to open without damaging the paper, so some of the text is missing. (I resisted the urge to prise them open, although the temptation was very real).

|

| Watermark faintly visible above the blot. |

There is a watermark – VG – which I have identified as most likely Valentino Galvani, [21] who was active in northern Italy in the late eighteenth century. [22] Galvani’s papers appear to have been used by Beethoven: archives in Berlin include Beethoven’s manuscript scores of Leonore. Galvani operated in Cordenons (still renowned for its paper making industry), Trieste and Pordenone, and died in 1797, however his papers remained in circulation for several years after his death. [23] The paper itself therefore suggests complex journeys of its own, from Northern Italy to Berlin and Glasgow, but also gives us an approximate date of the late 18th / early 19th century for the creation of our document.

|

| Top of Strathclyde GB 249 T-MIN/7 showing verses in Russian and Latin |

The handwriting is clear and easily legible despite some scratchings out and blots. Vocalizing the text under my breath in the University of Strathclyde reading room it became apparent that this was indeed a form of Russian, albeit one surely written for a reader, listener, or scribe with no knowledge of the Cyrillic writing system. Hence the title of this paper: the text was surely transmitted from mouth to ear, and brain to hand by two people involved in the creation of the document (the performer of the song, and the auditor for whom it was written down), and from eye to brain to voice when I read the document in the archive, and voice to ear when you hear it shortly. Yet the originators of the document, and the location and context in which it was created, are unknowable.

However, one area that could be investigated was the text itself: does it, as I hoped, make sense in Russian and Latin, or is it garbled nonsense, was it indeed a known song, and is there any music available for it?

I was, however, able to investigate the texts, and embarked on a parallel translation of Dr. Zvereva’s contemporary Russian text and the document’s Latin of c. 1806-1820 using the L'vov-Prach/Galvani / Beethoven dates into contemporary modern English using a combination of my rudimentary knowledge of Russian, schoolgirl Latin, Yandex, Tufts University Latin Word Study Tool, and Google Translate. Here is my result for the first verse; as you can see, the parallel translations from Russian and Latin into English are very similar.

|

The third verse is particularly curious, as there is no Russian text; ie it appears to be a creative extension of the poem. It leads towards a decidedly morbid conclusion.

Considering the question of music, one option that remains available to us is to return to the digital archives. Six years since viewing the original document I experienced a breakthrough in the form of Firefox’s new website translation app. Released on 11 February 2024, and still in Beta as at today’s date [11 April 2025], the app enables the translation of entire websites, thus facilitating the translation of a sizeable body of text about the possible location of the music for our lyric. There are, of course, several questions connected with digital archiving, including technical issues and the problem of who controls the process that creates an archive, which I have outlined elsewhere. [25] However, the translation app worked well for the purpose of generating an intelligible script.

Earlier this year I used the tool to translate the website suggested by Dr. Zvereva in 2019 and found a link to V. Kopylova’s Russian Canticles of the Eighteenth Century: Texts and notes of Russian cants of the 18th century for academic choirs. This has been reproduced on the Russian website Ale07.ru which, although anonymously produced, is very informative in terms of explaining the location of its source material, and scanning entire volumes of printed music, with their original introductions and endnotes. [26] In this case, Ale07.ru revealed that the song was part of a collection donated by A. A. Titov, now held at the Russian Academy of Sciences Library, and originally published in a Collection of Selected Old and New Russian Songs (St. Petersburg, 1803). [27]

The process of identifying the music wasn't entirely unproblematic, however. The sheet music for the entire Titov collection has been uploaded to Ale07.ru, however the edition provided was, on inspection, Kopylova’s critical edition published by Muzika in Leningrad in 1983, not a facsimile of the original 1803 publication, which I have yet to locate (although Dr. Zvereva has mentioned that several handwritten copies exist in the St. Petersburg archvies). Kopylova’s introduction (reproduced by Ale07) and notes on lexis and eighteenth-century Russian pronunciation explain that the song is ‘love-lyrical, in the character of a mobile minuet. It is recommended to be performed by a female trio, or with soprano, piano or harpsichord. One of the most popular [songs] in the 2nd half of the XVIII century.’ [28]

|

| Screenshot of V. Kopylova's 1983 'Leningrad text' edition of the song |

Looking at Kopylova’s edition, we are presented with some musical

inconsistencies: the song is scored for two upper voices and a bass, or

possibly soprano and keyboard, although the edition states ‘female

trio’. It is also unclear what a 'mobile minuet' might be: the adjective подвижного (mobile) suggests physical agility rather than emotionally moving or sentimental music. Without access to contemporary late eighteenth / early nineteenth century scores it is difficult to interpret how the music was intended to be performed, or if a degree of flexibility was anticipated in performance. For the purpose of creating a usable score, I made an editorial decision to revise the music for two soprano voices and an alto by transposing the bass part up an octave. As part of the rehearsal process it became apparent that the alto line did not work well with the bass octave jumps, so several of these were rescored. I also included a ficta in Bar 3 of the First Soprano part, to retain diatonic harmony in keeping with that of Haydn, Bortnyansky and other composers who were popular in Russia at this time. [29]

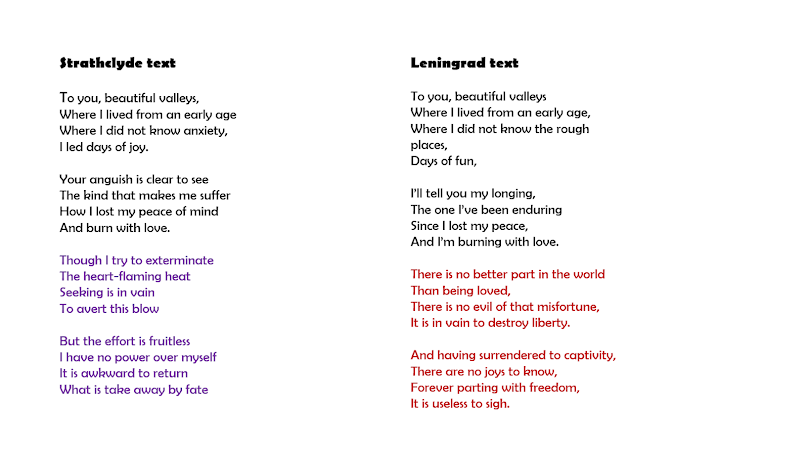

It is also apparent that there are some textual differences

between Kopylova’s ‘Leningrad’ edition and the handwritten ‘Strathclyde’

version, particularly in the latter section of the poem:

However,

while the texts clearly differ in the latter two stanzas, the key themes of fate, loss of childhood innocence, and loss of

freedom are consistent between both editions, and I propose they are

variants of the same song. It is possible that various manuscript

versions exist in manuscript, but for now, we must satisfy ourselves

with a reconstruction in 2025 of a 40-year old edition. This version for SSA was prepared using the text from the Strathclyde archive in order to

reproduce as closely as possible what our anonymous lyricist heard. This recording, made on Monday, 7 April 2025, is the SSA version. For possibly the

first time in 200 years, here is the mystery song from the Euing

Collection.

Singers: Kotryna Starkute (Soprano I), Dalia Gala and Jeanne Laborde (Soprano II), Esther Norie and Ashley Holdsworth Quinn (Alto). Recorded by Kenneth Tay with assistance from Cyrus Tan.

Notes

[1] The Berlin Wall came down eight days before my 15th birthday. My teenage years were filled with relief that nuclear Armageddon was increasing unlikely, and hope that encounters, musical and otherwise, between people who had previously been kept apart could start to happen.

[2] As of 9 January 2025 the SCAN website was decommissioned, and all material migrated to the National Records of Scotland web archive.

[3] See programme notes for a concert that included some of Henderson's transcriptions. Blest Are the Departed performed 12 November 2204 by the University of Glasgow Chapel Choir.

[4] Dunn, John. "1917 and All That: A History of Russian at Glasgow University." [In English]. Slavonica 22, no. 1-2 (2017): 54-64. https://doi.org/10.1080/13617427.2017.1405613.

[5] Dickson, Professor William P. "Biographical Notice of William Euing, Esq., F. R. S. E.". Obituary; biography. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh VIII, 91 (1 March 1875 1874-1875): 495. https://archive.org/details/per_proceedings-of-the-royal-society-of-edinburgh_proceedings-of-the-royal-socie_1874-1875_8_71/page/490/mode/2up

[6] https://www.lieder.net/lieder/get_text.html?TextId=135240 accessed 24 March 2025. Twenty-first century Ukrainain language sources are clear about the origins of the song, and an entry for Klimovsky is available in the Encyclopedia of the history of Ukraine in 10 volumes, ed. V. A. Smoliy (chairman) et al.; Institute of history of Ukraine of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. Moscow, 2007. See Vol.4 ISBN 978-966-00-0692-8. However it has proved difficult to identify attributed eighteenth or early nineteenth century Ukrainian sources for the music; the version in the L'vov - Prach compilation noted below identifies it as Ukrainian, but does not include the name of the composer. I'd be very grateful for any information about the earliest forms of the song.

[7] The best known is probably Variations for violin Op. 107 No. 7. He also included the song in a

collection commissioned by Edinburgh

publisher George Thomson. See Barry Cooper, Beethoven's Folksong Settings: Chronology, Sources, Style. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2023, https://go.exlibris.link/HqPB5nhm for the origins of Beethoven's folksong settings. He suggests Nikolai L'vov and Ivan Prach's collection of Russian Folksongs (St. Petersburg, 1806) as Beethoven's source for several Russian songs, but does not identify which; an examination of this collection reveals From the Danube is indeed included. See https://ks15.imslp.org/files/imglnks/usimg/e/eb/IMSLP619901-PMLP995813-Pra-,_Ivan,_sobranie_russkich_1.pdf for a reproduction of the 1806 original (attributed малоросс., ie Ukrainian, lit. 'Little Russian'), or Malcolm Hamrick Brown's 1987 edition for UMI Press, with new English introduction https://go.exlibris.link/HnkQW3k4.

[8] https://ks15.imslp.org/files/imglnks/usimg/8/81/IMSLP350937-PMLP566879-Magnien-op7.pdf Op. 7 accessed 24 March 2025.

[9] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qJA6yVpXcBY Flute trio Op. 78 accessed 24 March 2025.

[10] For example see Roger Fiske, Scotland in Music: A European Enthusiasm. Cambridge,

UK: Cambridge University Press, 1983.

https://go.exlibris.link/49mM5XC1 and Barry Coopers work listed above.

[11] Tsalik, Stanislav. ‘How Beethoven travelled

across the Danube’

http://sovremennik.ws/2008/01/14/print:page,1,jak_betkhoven_za_dunajj_zdiv.html accessed 11 March 2021.

[12] SCAN https://catalogue.nrscotland.gov.uk/scancatalogue/details.aspx?reference=GB249%2fT-MIN7&st=1&tc=y&tl=n&tn=y&tp=n&k=&ko=o&r=GB249%2fT-MIN7&ro=s& accessed 9 March 2025.

[13] https://webarchive.nrscotland.gov.uk/20250124111351/https://www.scan.org.uk/aboutus/report.htm#1 accessed 25 March 2025. Archived report commissioned by SCAN evaluating its initial success, dated 21 April 2004.

[14] SCAN website, www.scan.org.uk accessed 27 June 2019.

[15] Malm, Krister. "Music on the Move: Traditions and Mass Media." Ethnomusicology 37, 3 (1993): 13. https://www.jstor.org/stable/851718?seq=1.

[16] Negus, Keith, and Patria Román Velázquez. "Belonging and Detachment: Musical Experience and the Limits of Identity." Poetics 30, no. 1 (2002/05/01/ 2002): 133-45. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-422X(02)00003-7.

[17] Ther, Philipp. "Chapter 9 Comparisons, Cultural Transfers, and the Study of Networks toward a Transnational History of Europe." In Comparative and Transnational History, edited by Haupt Heinz- Gerhard and Kocka Jürgen, 204-25. New York, Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2010. 205.

[18] Heile, Björn. Musical Modernism in Global Perspective: Entangled Histories on a Shared Planet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2024. https://go.exlibris.link/B7ZQt54c.

[19] Cox, Arnie. Music and Embodied Cognition: Listening, Moving, Feeling, and Thinking. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2016. https://go.exlibris.link/hVws8QPD.

[20] Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. Metaphors We Live By. London & Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980.

[21] Online Watermark Databases/Catalogues." accessed 5 March 2025, https://www.paperhistory.org/Watermark-databases/

[22] "Valentino Galvani (1723-1797)." RISM, Updated 6 November 2024, 2016, rev. 2024, accessed 6 March, 2025, https://rism.online/people/30046988 (Biography of paper maker and supplier to the music industry).

[23]"My Cordenons Paper." accessed 8 April, 2025, https://mycordenons.com/

[24] Personal email, 1 March 2019.

[25] Holdsworth Quinn, Ashley. "‘Crisp as a Cream-Cracker’: Nikolai Orloff and British Musical Journalism in Memory of Stuart Campbell." [In English]. Muzikologija : časopis Muzikološkog instituta Srpske akademije nauka i umetnosti 2021, no. 31 (2021): 15-35. https://doi.org/10.2298/MUZ2131015H. https://go.exlibris.link/7vTpDm7F.

[26] https://ale07-ru.translate.goog/music/notes/song/chorus/text/kanty.htm?_x_tr_sl=ru&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=sc

accessed 8 April 2025.

[27] Библиотека Российской академии наук (Bibioteka Rossiyskoi akadmii nauk) Tit., 4070, l. vol. 43.

[28] Personal email 1 March 2019.

[29] See Gerald Seaman's article "Amateur Music-Making in Russia" for a description of music popular with the aristocratic classes in late eighteen and early nineteenth century Russia. Music & Letters 47, no. 3 (1966): 249-59. http://www.jstor.org/stable/732400.

Biography

Ashley Holdsworth Quinn is currently writing a PhD thesis at the University of Glasgow on the theme of music and conflict, focussing on choral practice in Scotland during the period 1914-1919. Her interests include varied embodied forms of cultural activity, from choral singing to textile craft. She is currently the President of Cappella Slavonica Scotiae, and also sings with the University of Glasgow Chapel Choir.

.png)

Comments

Post a Comment